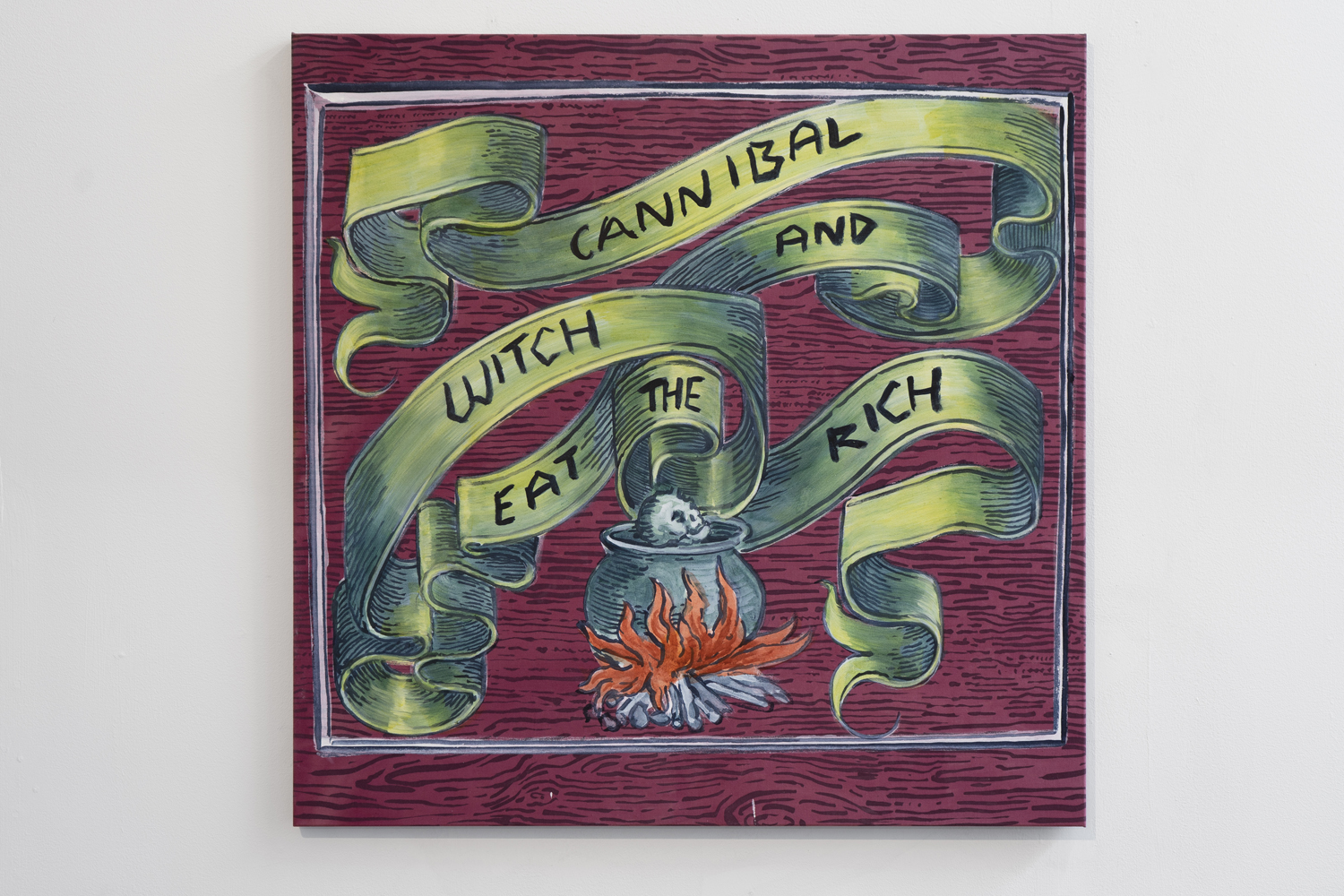

Cannibal and Witch Eat the Rich

Scroll gallery below for more images ︎︎︎︎︎︎

This exhibition of paintings and printed textiles made

using earths and plant dyes, follows the colonial histories and stories of

resistance belonging to these materials. It took place at Celsius Projects, Malmö, in 2021. It was part of the final exam for

my PhD research project “The Peasant Paints: expanding painting

decolonially through planting and pigment-making” undertaken at Goldsmiths

College, University of London.

More information about the practice-based research can be found at www.thepeasantpaints.picturesMy thesis can be downloaded ︎︎︎here

More information about the practice-based research can be found at www.thepeasantpaints.picturesMy thesis can be downloaded ︎︎︎here

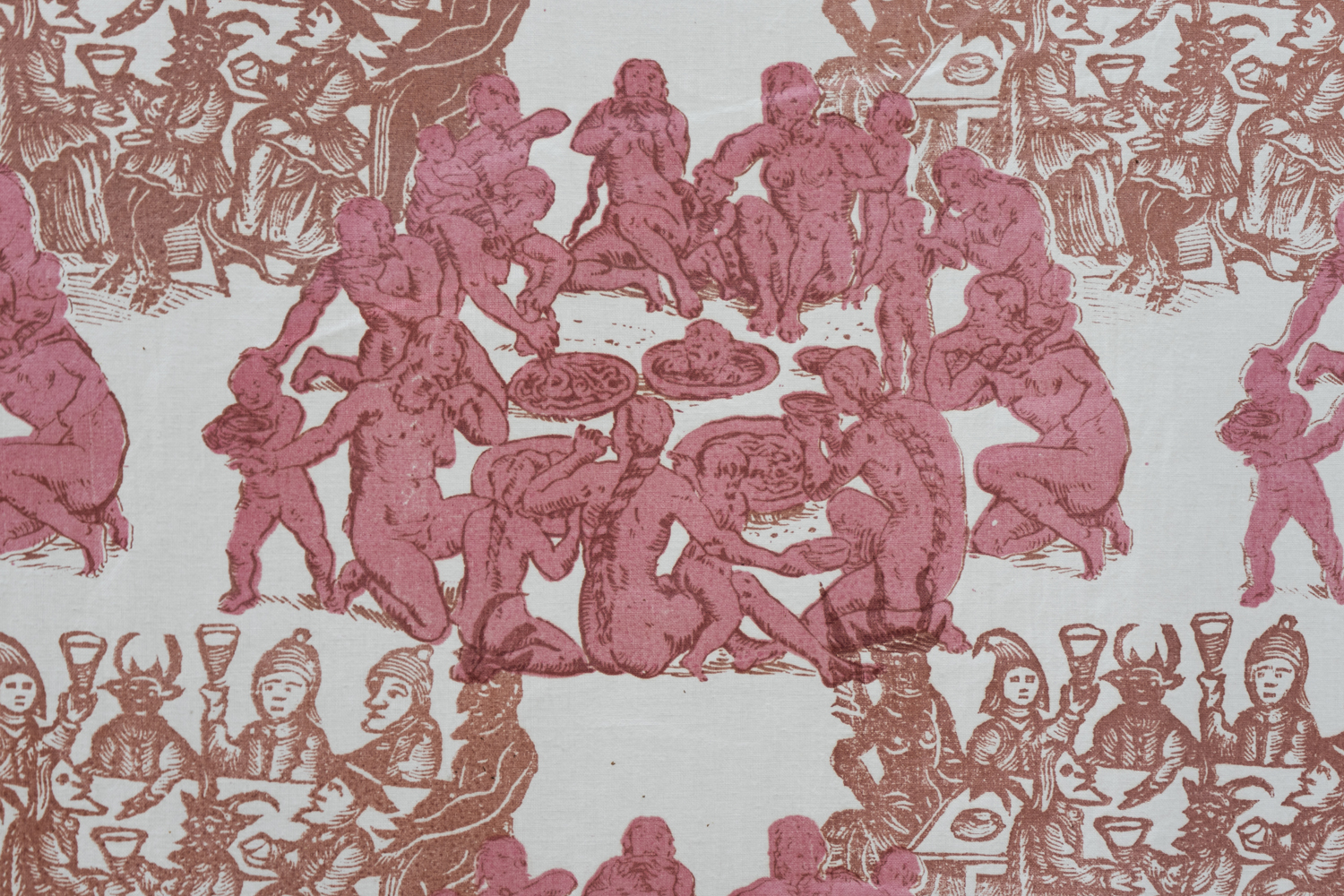

Printed calicos from India using

plant dyes and mordants on cotton fabric were a particularly popular commodity in Europe from the 17th century, until many countries

introduced import bans to support local industries during the 18th

century. These European calico printers appropriated the Indian techniques, and

used plant dyes from around the globe such as indigo from grown with enslaved

labour in the Americas, and later India, under the plantation system; and

brazilwood and logwood from the rainforests of Central and South America. These

patterned calicos formed an integral part of Swedish regional costumes in the

form of headscarves, aprons, and linings for bodices – thereby demonstrating

that the figure of the peasant that has been used to construct ideas of

nationhood in Scandinavia, was in fact implicated in global colonial forces.

Western colonialism and capitalism with its extractive

approach to plants as ‘natural resources’ served to suppress alternative ways

of relating with plant-beings both within Europe and outside Europe. As Silvia

Federici has argued in her book Caliban and the Witch, the Great Witch Hunts,

in particular, were a counter-revolutionary tool that served to supress radical

movements from the peasant class, and appropriate women’s reproductive

capacities by silencing their medicinal knowledge of plants. This tactic was

then exported to the Americas to suppress indigenous knowledge through

accusations of satanism and idolatry. The works in this exhibition use plant

pigments and dyes that have particularly resonant stories, such as Mayan blue –

a sacred pre-Colombian indigenous pigment made from indigo and attapulgite clay

that ceased to be made during the oppression of the colonial period and has

only recently been ‘re-discovered’ – and brazilwood, a tree which produces a

red dye, and which gave the country of Brazil its name.

The birth of the brazilwood trade in

the 16th century is a devastating example of bioprospecting which

exploited the Tupi Amerindians, who were depicted as savage cannibals by

Europeans and decimated the brazilwood trees leaving it endangered to this day. Meanwhile, in

Europe brazilwood was very much implicated in the disciplining of a new

proletariat. The displacement of peasants in the wake of agrarian capitalism

meant that many moved to urban centres and became beggars and vagrants. In response, the authorities in Amsterdam, set up a new form

of prison that used forced labour to discipline and reform these vagrants of

rural origin. In 1596 the Rasp- and Spinn- huis was established, and functioned

until 1815. Here, male inmates were set to work rasping brazilwood for the dye

and pigment industry, while women were forced to spin and weave textiles. This

model was eventually copied elsewhere in Europe, with rasp- and spinn- hus

being set up in Copenhagen, Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Norrköping during the

eighteenth century.

This exhibition imagined an alternative history with an alliance between the cannibal and the witch to eat the rich.

This exhibition imagined an alternative history with an alliance between the cannibal and the witch to eat the rich.